|

Guest Column by Joshua Marquis

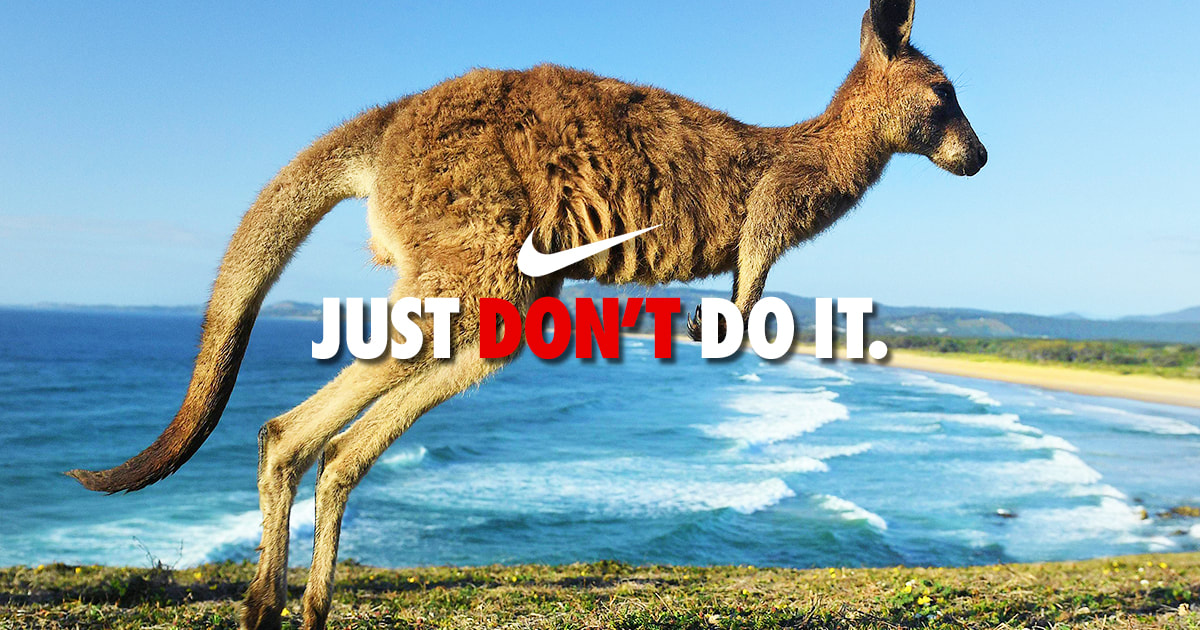

Bend Bulletin July 4, 2022 When we think of kangaroos in the United States, the last thing we would imagine is the savage butchering of a mother kangaroo and the subsequent abandonment, starvation, or killing of her “joey” or dependent young kangaroo she famously carries in a pouch. Most of us, even those involved in animal protection, had little idea that an iconic, and often beloved Oregon-based company (Nike) was keeping alive a gruesome niche market where these animals are butchered for high-end running shoes. You may be hearing for the first time the popular purveyor of athletic gear supports the inhumane and unnecessary destruction of native wildlife overseas. When you hear the ugly details of how these shoes are made, you will likely want to join me at the next protest — as Oregonians did earlier this month in Portland — or do something else to help. Mother kangaroos are shot with joeys growing inside their pouches or standing by their sides for protection. The Australian government with its National Code of Practice for the Humane Shooting of Kangaroos and Wallabies for Commercial Purposes instructs shooters to either decapitate or bludgeon to death the surviving young. If that’s humane, then what is inhumane? California is the only state that bans sales of shoes made from kangaroo skins, including soccer cleats by Nike, as well as athletic shoes by Puma and Adidas. Yet Nike and these other companies are still selling shoes made from kangaroo skins with impunity, because nobody is enforcing the law. Based on two years’ worth of investigation, the Center for a Humane Economy published a report, “Skin in the Game: An Investigation into the Illegal Trade of Kangaroo Parts in California” showing that many soccer shoe retailers continue to sell kangaroo cleats from companies like Nike, Adidas, and Puma. This is despite our efforts at encouraging enforcement of the law by reaching out to countless law enforcement officials and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Mindful of that inaction, recently, the Center for a Humane Economy and its affiliate Animal Wellness Action, sued Soccer Wearhouse, a California retailer with three locations in Southern California, to permanently enjoin their sale of kangaroo cleats. Mindful of that inaction, recently, the Center for a Humane Economy and its affiliate Animal Wellness Action, sued Soccer Wearhouse, a California retailer with three locations in Southern California, to permanently enjoin their sale of kangaroo cleats. We don’t slaughter our dogs, cats, or horses for meat in this country; we have stopped buying fur from trapped or farmed animals. Now it is time to apply those same evolved ethical standards to help save the kangaroos in Australia from a cruel and callous industry that elevates profits above compassion and conservation. ####END Guest column: Stop slaughter of kangaroos for shoes | Opinion | bendbulletin.com People’s tastes and values can change over decades. Mink have an almost unique susceptibility to COVID-19, getting it from and spreading it to humans. Mink farming is an industry whose day is done. Animal Wellness Action encourages the buyout of mink farms.

Guest column for The Astorian January 15, 2021 "The time for mink farms has passed" Contagious not just to people, COVID-19 is devastating captive mink populations across the world. Prominent veterinarians and scientists believe mink are almost uniquely capable of animal to human transmission. There is even concern that such transmission could create a mutant strain of COVID that would be resistant to the vaccine. Clatsop County is home to two mink farms, both legal businesses. The Oregon Department of Agriculture disclosed that a mink farm was placed in quarantine in November after a farmer and several mink tested positive for the virus. The state has not publicly disclosed the location of the farm, citing medical privacy reasons. While the state veterinarian said there was “no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is in circulation or has been established in the wild,” others pointed out that makes it appear infected mink escaped. In December, The New York Times reported on the extraordinary events related to mink farming and COVID-19 cases from Denmark: “Not only are mink the only nonhuman animal known to become severely ill and die from the virus, they are the only animal known to have caught the virus from humans and then passed it back. What terrified Danish officials was that the virus that jumped back to people carried mutations that seemed as if they might affect how well vaccines work, although that worry has faded.” In response to a series of outbreaks from Denmark to Greece to Lithuania, European countries have conducted mass slaughters of thousands of the animals, with an astonishing 17 million mink killed in Denmark alone. The Netherlands has taken it a step further. There, the government has banned all fur farming effective in March. While concerns over animal cruelty were factors in the original discussion, the impetus for the expedited action was the concern about mink farms becoming superspreader venues. The concerns about mink farming and COVID-19 warrants immediate action in the U.S., just as we’ve seen in Europe. But even without that perilous circumstance, there are plenty of good reasons to ban fur farming. It is an outdated business, much like ivory harvesting, Styrofoam packaging and cigarette advertising. As we are told in a widely accepted text of spiritual wisdom, “For everything there is a season.” For our health and out of respect for the nearly universal aversion to animal cruelty, government should begin a buyout of all mink farms, fairly compensating the breeders and permanently ending the practice. This process has been used in other parts of the world to discourage farmers of plants like coca and poppies that are easily made into cocaine and heroin. The world is replete with examples of past practices considered commonplace, if considered at all, that for reasons relating to health, the environment or changing sensitivities, are simply no longer appropriate. There is no need to engage in moral virtue signaling, either by condemning those who wear mink, or by refusing to acknowledge that mink farming has been a legal industry. As Wayne Pacelle, president of the Center for a Humane Economy notes, “Minks are superspreaders of this virus. They are also wild animals, and they don’t belong jammed in cages on factory farms.” Joshua Marquis, a former Clatsop County district attorney, is director of legal affairs for Animal Wellness Action.  from Animal Wellness Action from Animal Wellness Action Portland Tribune, August 12, 2020 Joshua Marquis and Emily Ahyou 'We should expect companies like Nike ... to adapt and end their role in driving the slaughter of kangaroos.' Some older runners may recall a time when kangaroo skin was used in some running shoes, but are surprised to learn that, while greatly diminished, the practice still exists. A number of footwear giants, most significantly including Oregon's own Nike, the iconic brand founded by Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman. But Nike isn't alone in this reprehensible practice. Adidas, New Balance and Puma are among a dozen companies still using "K-leather," particularly for soccer cleats. Most of us find kangaroos charming. They're sociable boxers. The females carry their babies around in a pouch. They pose no threat to humans. The recent catastrophic fires in Australia called attention to these remarkable creatures, alerting the world to the effects of climate change and their fragile existence when their habitats are aflame. Even before the fires raged, these iconic symbols of Australia were the victims of human callousness and cruelty. The government blesses an annual massacre, conducted by commercial hunters, of upwards of 2 million kangaroos per year. The hunting practices are ruthless, often occurring at night, with the hunters shining a light on the marsupials and trying to shoot them in the head. If the victim is female, and lactating, there's an additional casualty: a "joey" yanked from the pouch and decapitated or swung by the legs onto a rock to bash in its head. Just as America protects the bald eagle, Australia must do better when it comes to kangaroos. The recent fires are a reminder of what's at stake. The state of California has banned the sale of shoes containing kangaroo leather, but buyers can still find them. But most consumers remain largely unaware of their role in wildlife exploitation, since the athletic shoe industry doesn't often explicitly label its fabrics. China has finally acknowledged that the rest of the world is repulsed by the dog-meat industry there, and we should expect companies like Nike, which highlight their social consciousness in advertising and as part of their corporate culture, to adapt and end their role in driving the slaughter of kangaroos. Nike and other companies already offer soccer cleats made from synthetic or plant-based fibers. There was a time when we slaughtered bison by the billions and hunted other species into extinction. That is an ugly era in our treatment of wildlife, and the kangaroo slaughter seems more than a little bit misplaced in the 21st century. Corporate talk of sustainability and social consciousness must have practical features. Those representations fall flat when you consider the company is behind the largest mammalian slaughter of wildlife in their native habitats in the world. The slaughter of kangaroos plays no legitimate role in Nike's corporate culture. It is instead something that any sane person or company would conceal and minimize. But in our era of global communications, there's no way to hide a body count of this scale. It's time for Nike to blaze a humane path and help push the take the entire industry out of the business of mass wildlife killing. Just do it. Joshua Marquis is director of legal affairs for Animal Wellness Action and lives in Astoria. Emily AhYou is Oregon state director of Animal Wellness Action and lives in Clackamas. ###  downtown Portland, Aug 6, 2020 downtown Portland, Aug 6, 2020 Mary Ann Murk, an attorney in Astoria, Oregon, is probably the best and savviest advocate a person facing a mental commitment could have. She writes honestly about the cruelty that some allegedly mentally ill persons are subjected to, and the costs of and emotional burden to the law enforcement officers charged with finding some place for the person to land. These people haven’t been charged with a crime. Their victims are often family members who want them to get help, not spend time in jail. Oregon’s law on allegedly mentally ill persons (colloquially known as AMIPs) has nothing to do with legal insanity or being unfit to stand for trial. The mental commitment process isn’t part of the criminal code. It’s an attempt to provide a constitutional structure for people suffering such severe mental illness that they pose an immediate physical threat to themselves or others, or who won’t provide for such a basic need as eating.

These cases are heartbreaking. They are usually brought by concerned family members, rarely by the cops, never by the district attorney’s office. Here’s a fairly typical example: A family member repeatedly calls Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare (CBH) because their adult son is convinced outside governments are communicating with him through microwaves that only he can hear. One day he threatens to blow up a local government building to stop the voices. He yells, screams, takes out the kitchen knives and begins cutting himself. A crime hasn’t been committed. The police won’t engage, even if the family says they’re afraid of what the son might do. CBH will send one or two case workers to assess the situation and write a report. If they believe the son meets the qualifications, CBH will apply to the court for an order. If the judge believes the person qualifies under Oregon law, she will sign a warrant of detention. At this point the sheriff’s office is delegated the responsibility of transporting the person to whatever mental hospital between Coos Bay and the Idaho border is available. Let’s say the person is “decompensating” -- falling apart -- in a store. Making a terrible and frightening scene but not destroying any property. The store is likely to call the police. The police will likely come to ensure a crime hasn’t taken place. This is one of the social services we’ve come to expect the police to provide. They will try to “de-escalate,” or calm down, the person, and possibly suggest he leave the store. Police are trained in de-escalation. The officer is there to make sure no one is getting hurt and that the guy doesn’t have a weapon. Once the officer has assured that, she will call CBH to have that agency come and assess the person. Often CBH doesn’t or can’t immediately respond, so the officer has to stay around to make sure the person is safe and that the situation doesn’t escalate. If the officer can articulate an imminent danger, she can hold the person temporarily, usually in the back of the police car, until CBH arrives. There are many scenarios. Some are worse -- for everyone -- than others. The important point here is that police don’t investigate and make judgments about mental illness. Mental health workers do. The budget of CBH is larger than the sheriff’s office and the district attorney’s office combined. (All CBH funding comes from the state and some federal sources.) And yet we definitely need more funding for mental health. We also need the police, and probably more funding for them, at least in Astoria. I can guarantee you that if a family member calls CBH and says their son has lost his mind and is waving a butcher knife around, CBH is going to call the police, and wait for officers to respond before going in themselves. (That’s one other reason why officers wear 40-pound vests: to prevent themselves from being stabbed in the chest.) No mental health facility for those who need temporary commitment is available anywhere on the north coast. Semi-independent housing was closed years ago. Drop-in crisis services have been dramatically reduced. Neither our hospitals nor our jail have a room for people whose primary issue is acute mental illness (despite years of attempting to convince both CMH and Providence Seaside to do so.) The Oregon State Hospital was massively downsized over a decade ago. The only options are within a small patchwork of hospitals ranging from Coos Bay, Corvallis, Portland, and Ontario. A shackled 9-hour ride in the back of a sheriff’s patrol car is demeaning and terrifying, as most of the people are in active psychosis and believe they are being abducted by aliens or sent for medical experiments. They are clearly suffering and usually haven’t committed a crime, and certainly haven’t been charged as yet. Nor should the sheriff have to engage in this sometimes dangerous and almost always unpleasant duty. What can we do? Mandate that all hospitals have the ability to do psychiatric evaluations every day of the week. Create a treatment and evaluation facility close enough to avoid the long ride. Assign transport to a non-police agency. But consider what might happen when the allegedly mentally ill person attacks the driver or bolts the car on the Santiam Pass in mid-winter. Once social workers have the training, legal authority, and desire to run after and restrain someone in the grip of a psychosis, they might as well be police officers. There are many dedicated people working in the field, but we fail the profoundly mentally ill. The police are the least culpable of all. Some proponents of Defund the Police want to refocus how police work is done. Many police departments themselves might welcome this because many consider the proper work of police to be detecting and apprehending criminal suspects, not doing social work. Some proponents, like the city leaders in Minneapolis and Seattle, have made clear they seek abolition. In practical terms that will mean that unless an actual crime is underway, and likely a violent crime, police officers will respond only to purely criminal calls. That, of course, does nothing to avoid confrontations with robbers high on meth, and men with anger management problems who’ve beaten their girlfriend to a bloody pulp. A serious car crash might be ignored absent immediate evidence of drunk driving. Police reforms, treatment of the mentally ill -- these issues should go well beyond politics. The Great Cauliflower, as I’ve often called Reagan, didn’t open the mental institutions on his own. Nor did Nixon. The call to deinstitutionalize came well before either of these conservatives, and arose from more liberal outrage. Ken Kesey’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” was published in 1962. In 1963 Kennedy proposed and signed into law the “Community Mental Health Act,” which would have built local mental health facilities to replace institutions. The Act was poorly funded due to the costs of the Vietnam War. Medicaid’s passage in 1965, signed into law by Lyndon Johnson, incentivized moving patients out of institutions. Just as former speaker of the house Tip O’Neill said, “All politics is local.” By extension, so are the solutions. ###  from Animal Wellness Action from Animal Wellness Action Animal Wellness Action Press Release Animal Wellness Action welcomes Joshua Marquis as Director of Legal Affairs and Enforcement For Immediate Release:Contact: Marty Irby • 202-821-5686 [email protected] Marquis will promote the enforcement of animal protection laws and form a national law enforcement council focused on animal issues Washington, D.C. — Animal Wellness Action (AWA) is pleased to announce that Joshua Marquis has joined the group as Director of Legal Affairs and Enforcement. An experienced prosecutor with an accomplished record on animal protection cases, Marquis will help coordinate efforts by AWA to bring state and federal laws against animal cruelty into the 21st century and empower efforts to use the law to protect animals. “Josh Marquis has a unique mix of skills as a trial lawyer and a fierce public advocate, bringing special skills to the task of fortifying the legal framework against animal cruelty,” said Marty Irby, executive director of Animal Wellness Action. “Marquis’ 35 years of commitment to fighting animal abuse and neglect will help create partnerships that cross traditional political and professional divides.” Marquis retired in December 2018 after serving seven terms as elected District Attorney of Clatsop County (Astoria) in Oregon. He was both chief trial prosecutor and administrator of the largest law firm in the county and personally tried hundreds of jury trials, including numerous animal cruelty cases. Marquis developed a reputation for a passion for animals during his terms as Chief Deputy District Attorney in Newport, Ore and Bend, Ore. One of his first cases in Astoria was against Vicky Kittles, a woman hoarding a school bus full of cats. Marquis made animal abuse a state legislative issue and was a driving force behind an upgrade of the state’s anti-cruelty law in the mid-1990s to make malicious cruelty a felony. Well-known for his straight-talking nature, Marquis has testified before the Congress half a dozen times, spoken dozens of times across America on topics relating to law and contemporary society, has contributed many opinion pieces to the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal and others, is a regular guest on national radio and television programs, and is the author of several widely-referenced law review articles. Marquis previously served on the Board of Directors of the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF). He co-chaired the Media Relations Committee for the National District Attorney’s Association, in which he remains a member. He has received national recognition for his work for his years of work advocating for more effective laws regarding animal cruelty. Marquis is a graduate of the University of Oregon Honors College and the University of Oregon Law School. Animal Wellness Action (Action) is a Washington, D.C.-based 501(c)(4) organization with a mission of helping animals by promoting legal standards forbidding cruelty. We champion causes that alleviate the suffering of companion animals, farm animals, and wildlife. We advocate for policies to stop dogfighting and cockfighting and other forms of malicious cruelty and to confront factory farming and other systemic forms of animal exploitation. To prevent cruelty, we promote enacting good public policies and we work to enforce those policies. To enact good laws, we must elect good lawmakers, and that’s why we remind voters which candidates care about our issues and which ones don’t. We believe helping animals helps us all.

|

JOSHUA MARQUIS on

criminal justice, animal welfare, and the nature of the relationship between popular culture and the law. Archives

March 2024

See the Archives page for an index of all posts, including those prior to January 2019.

Categories |